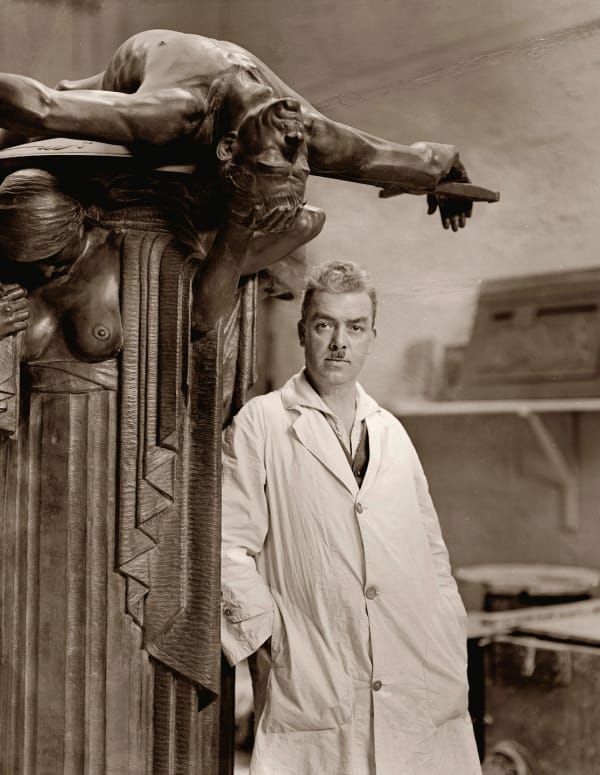

Ask sculptors to nominate the single greatest work of Australian sculpture and most will opt for The Sacrifice (1934), the centrepiece of the Anzac Memorial in Sydney’s Hyde Park. It is the work of Rayner Hoff (1894-1937), an exceptional artist and inspirational teacher.

Photo: Harold Cazneaux

Hoff was born on the Isle of Man, the son of a stone mason. The family moved to Nottingham while he was still a child. Hoff would study at the Nottingham School of Art until interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. In the army his drawing skills got him assigned to a Field Survey Company, where he was given the task of preparing detailed maps of the battlefields.

After the war Hoff transferred to the Royal College of Art, London, and became a star pupil. He had graduated and visited Rome, when he was invited to apply for a post as a teacher of antique drawing and sculpture at Sydney Technical College.

After migrating to Sydney in 1923, he became an acclaimed artist and teacher. His war memorial sculptures in Australia have come to represent the spirit of ANZAC in his adopted country.

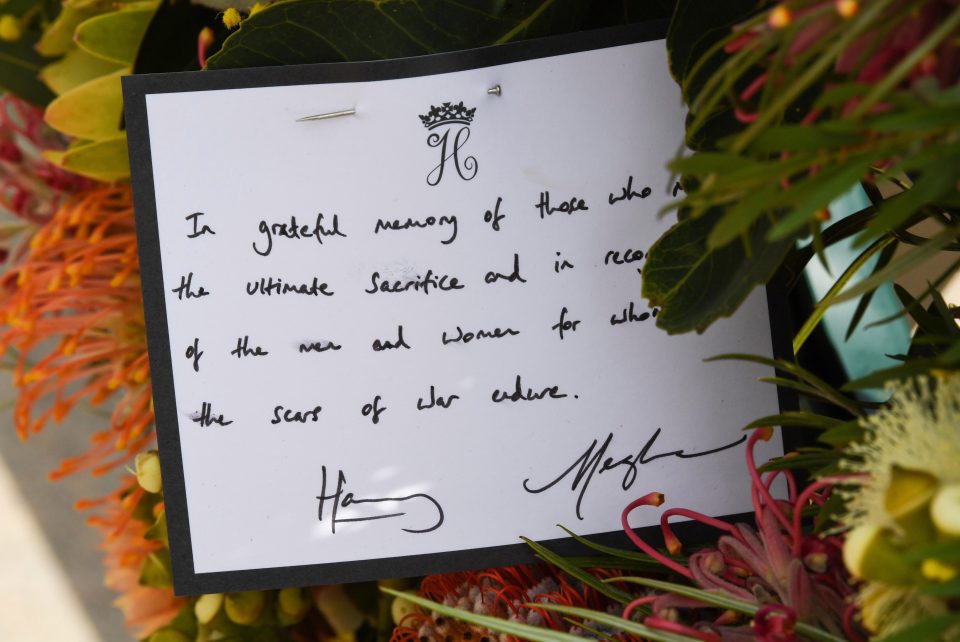

The royal couple arrived at the south end of the memorial on Liverpool Street about 10am, walking past new water cascades conceived in the original design but never completed, because of the financial hardships of the Great Depression.

For Prince Harry, being able to visit and officially open the newly renovated sections represented a royal step back in time; his great-great uncle and namesake, Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester – who later went on to become Australia’s 11th Governor-General – originally opened the building in 1934.

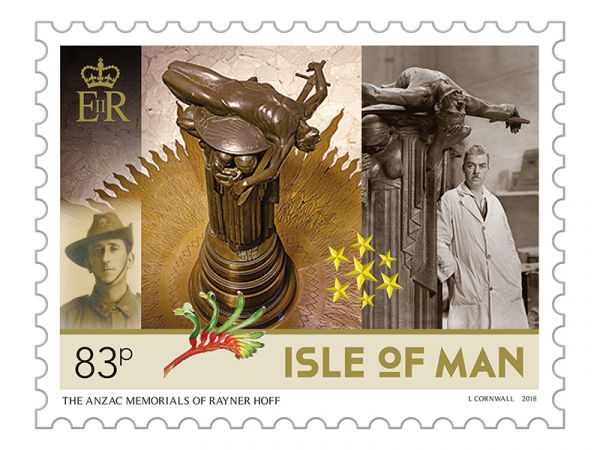

ANZAC Memorials of Rayner Hoff

These stamps were designed by Australian designer Louise Cornwall in association with author Deborah Beck who recently collaborated on Rayner Hoff – The Life of A Sculptor, which tells the story of Hoff’s life and work for the first time, and how he spearheaded an Australian sculpture renaissance and left a mark that is still keenly felt today.

Rayner Hoff created a sculpture that depicts the weight of the dead young warrior carried on his shield by his mother, sister and wife nursing infant child. The Sacrifice uses the analogy of the Spartan warrior being returned to his loved ones dead on his shield to evoke the emotion experienced by the families of the young men who died in the Great War 1914-18.

Spartan men were raised as warriors from boyhood and, when marching to war, were told to come home with their shield or on it – a warning to be victorious or die in the attempt.

“Another woman handed her son his shield, and exhorted him: ‘Son, either with this or on this.’”

Quote from Plutarch in Sayings of Spartan Women.

The Roman writer Plutarch was a Greek, born approximately 46 AD in the town of Chaeronea in the region of Boeotia. He is not a contemporary source of the saying, as the days of Spartan military glory had ended more than three centuries earlier.

Because of its size and sturdiness, a shield did make a good battlefield stretcher — and if the shield used for that purpose belonged to the stretchee, no one else needed to go unprotected. Carrying someone back on his shield served another purpose as well. A shield was one of the more complicated and valuable parts of a Greek hoplite’s armour. It and other items of equipment were traditionally passed down from father to son, brother to brother, or even uncles to cousins. Families of a warrior culture such as the Spartans depended on re-use of the family shield if possible.

The shield was made of multiple layers of metal (bronze, copper, or sometimes tin), wood, and tough linen, cloth, or leather, and could weigh as much as 15 to 20 pounds. In the Greek battle formation known as the phalanx, the shield protected not only the warrior holding it (while leaving his right arm free to wield a spear), but also the warrior on his left. A phalanx that stayed in tight formation was well protected by the interlocking shields.