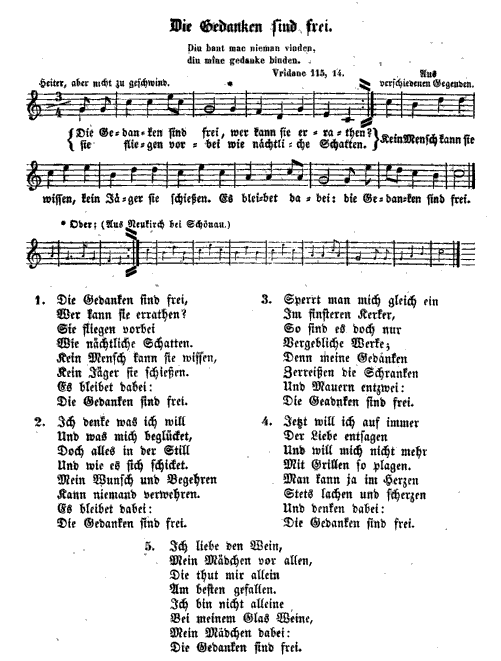

Thinking for oneself is a difficult and lifelong undertaking.

In her new book, Why Grow Up?: Subversive Thoughts for an Infantile Age the philosopher Susan Neiman takes on the predicament of maturity, that dates back to the 18th century.

Source: ‘Why Grow Up?’ by Susan Neiman

An American born philosopher who lives in Berlin, Neiman wants you to think for yourself.

The “infantile age” she has in mind goes back to the 18th century, and its most important figures are Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant. “Coming of age is an Enlightenment problem,” she writes, “and nothing shows so clearly that we are the Enlightenment’s heirs” than that we understand it as a topic for argument and analysis, as opposed to something that happens to everyone in more or less the same way. Before Kant and Rousseau, Neiman suggests, Western philosophy had little to say about the life cycle of individuals. As traditional religious and political modes of authority weakened, “the right form of human development became a philosophical problem, incorporating both psychological and political questions and giving them a normative thrust.”

How are we supposed to become free, happy and decent people?

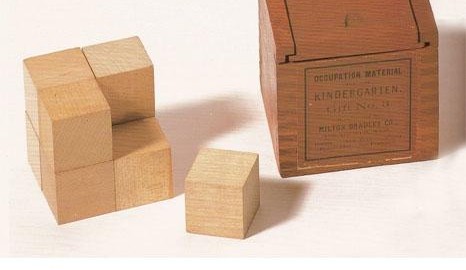

Rousseau’s “Emile” supplies Neiman with some plausible answers, and also with some cautionary lessons. A wonderfully problematic book — among other things a work of Utopian political thought, a manual for child-rearing, a foundational text of Romanticism and a sentimental novel — it serves here as a repository of ideas about the moral progress from infancy to adulthood. And also, more important, as a precursor and foil for Kant’s more systematic inquiries into human development.

The Geneva born Rousseau traveled across Europe on foot, fathering and abandoning at least five children. Kant rarely left his native Königsberg and never married. Between them, they mapped out what Neiman takes to be the essential predicament of maturity, namely the endless navigation of the gulf between the world as we encounter it and the way we believe it should be.

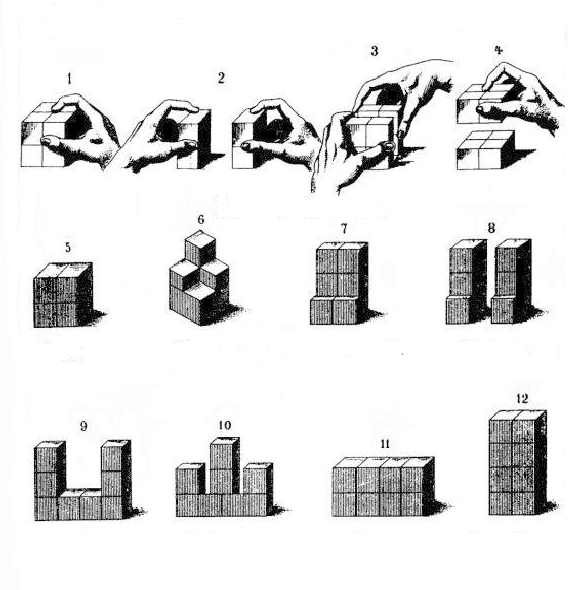

In infancy, we have no choice but to accept the world as it is.

In adolescence, we rebel against the discrepancy between the “is” and the “ought.”

Adulthood, for Kant and for Neiman, “requires facing squarely the fact that you will never get the world you want, while refusing to talk yourself out of wanting it.” It is a state of neither easy cynicism nor naïve idealism, but of engaged reasonableness.