Frederick William III of Prussia at first seriously considered ways of fulfilling the promise he had made in 1815 to establish constitutional government.

Economic reformers succeeded in enacting the Prussian Customs Law of 1818, which united all the Prussian territories into a customs union free of internal economic barriers; this later formed the nucleus of a national customs union.

To those, whose hopes had risen so high during the Wars of Liberation, the peace settlement of 1815 seemed to be an instrument of blind reaction.

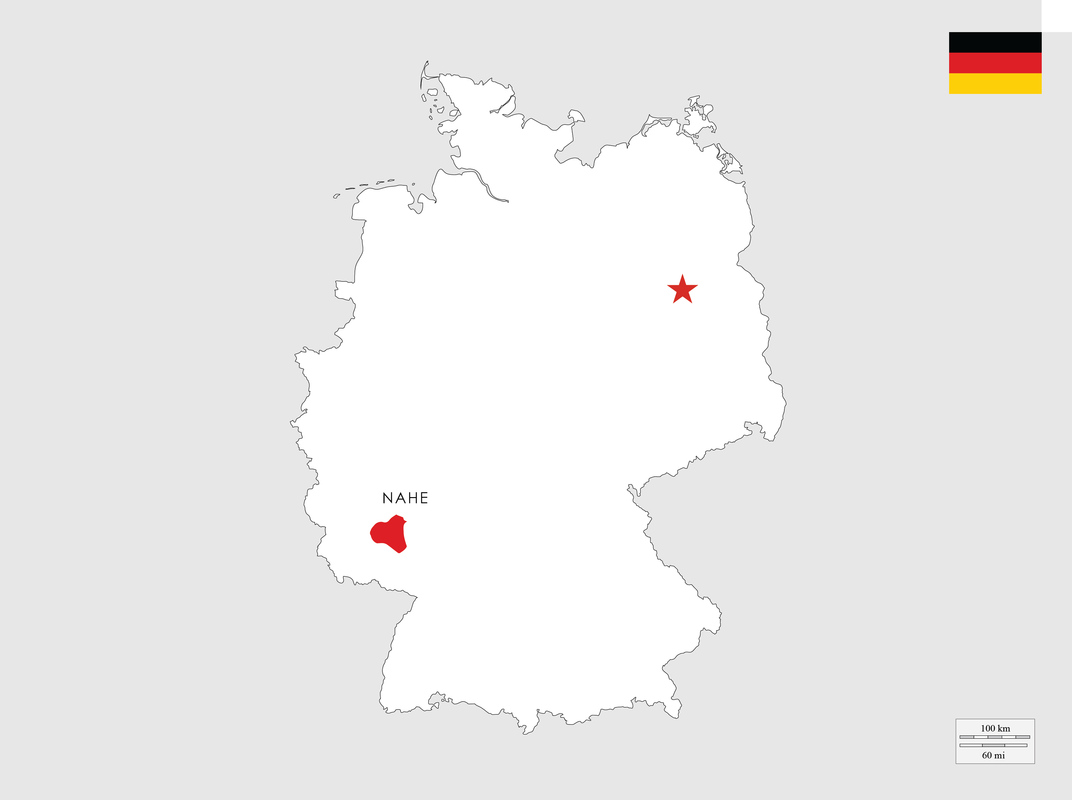

In place of the Holy Roman Empire the peacemakers of the Congress of Vienna had established a new organization of German states with a federal Diet meeting in Frankfurt am Main. Delegates were appointed by and responsible to the rulers whom they served.

By the end of 1820 the reform movement came to a complete halt. It had succeeded in altering the political and economic structure of society, but it had been unable to establish a tradition of liberal government and national loyalty in Germany.

Although the critics of the established order could be defeated, they could not be silenced. There were now men in the German states who refused to submit without question to princely authority and to seek freedom only in the inner recesses of the soul.

The liberals, or moderates favoured a monarchical system of authority, but the crown was to share its powers with a parliament elected by the men of property. Influence in public affairs should be accessible to all male citizens who had demonstrated through the acquisition of wealth and education that they were capable of exercising the franchise intelligently. Their path of civic wisdom was the happy medium between royal absolutism and mob rule, a medium that had been established in Britain by the Reform Bill of 1832 and in France by the regime of Louis-Philippe. The liberals favoured the transformation of the German Confederation into a national monarchy in which the states’ rights would be curtailed but not destroyed by a central government and a federal parliament.

The democrats, or radicals, looked with scorn on the golden mean between autocracy and anarchy that the liberals sought. They preferred an egalitarian form of authority in which not parliamentary plutocracy but popular sovereignty would be the underlying principle of government. While they were forced to accept the crown as a political institution, they nevertheless sought to transfer its power to a parliament elected by universal male suffrage. While not as influential as the moderates, the radicals remained an important source of opposition to the established order.

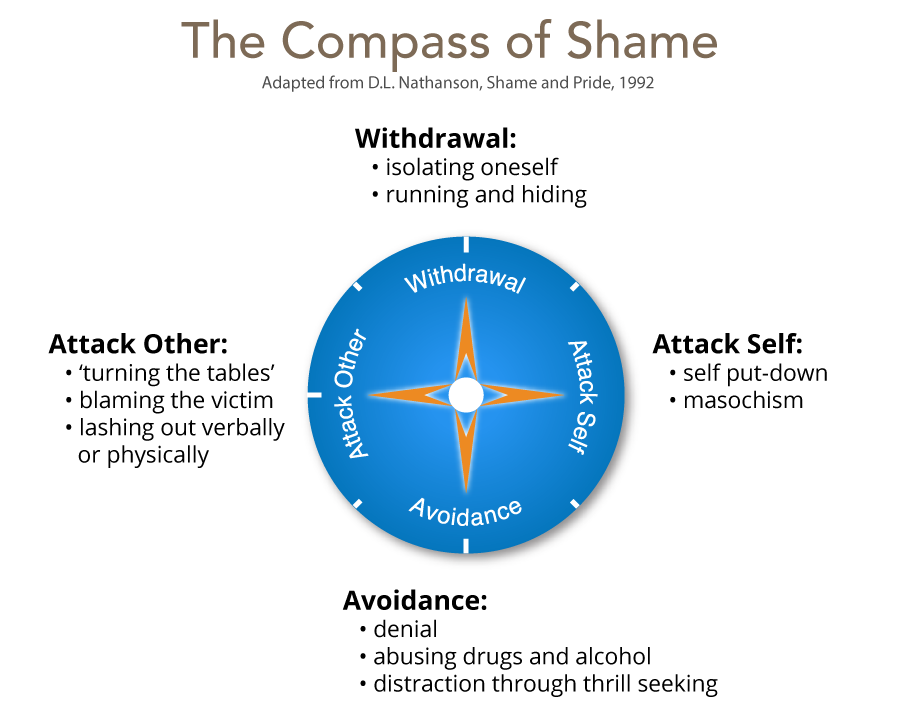

Growing criticism of the restored political order forced conservatives to define their ideological position more precisely. The old theories of monarchy by divine right or despotic benevolence offered little protection against the assaults of liberalism and democracy. The defenders of legitimism began to advance new arguments based on conservative assumptions about the nature of man and society.

The relationship between the individual and government, so the reasoning went, cannot be determined by paper constitutions founded on a doctrinaire individualism. Human actions are motivated not solely by rational considerations but by habit, feeling, instinct, and tradition as well. The impractical theories of visionary reformers fail to take into account the historic forces of organic development by which the past and the present shape the future. An enduring form of government can be built only on the traditional institutions of society: the throne, the church, the nobility, and the army. Only a system of authority legitimated by law and history can protect the worker against exploitation, the believer against godlessness, and the citizen against revolution. According to these tenets, the political institutions of the German Confederation were valid, because they represented fundamental ideals deeply embedded in the spirit of the nation.

The hard times that swept over the Continent in the late 1840s transformed widespread popular discontent in the German Confederation into a full-blown revolution. After the middle of the decade, a severe economic depression halted industrial expansion and aggravated urban unemployment. At the same time, serious crop failures led to a major famine from Ireland to Russian Poland. In the German states, the hungry 1840s drove the lower classes, which had long been suffering from the economic effects of industrial and agricultural rationalization, to the point of open rebellion. There were sporadic hunger riots and violent disturbances in several of the states, but the signal for a concerted uprising did not come until early in 1848 with the exciting news that the regime of the bourgeois king Louis-Philippe had been overthrown by an insurrection in Paris (February 22–24). The result was a series of sympathetic revolutions against the governments of the German Confederation, most of them mild but a few, as in the case of the fighting in Berlin, bitter and bloody.

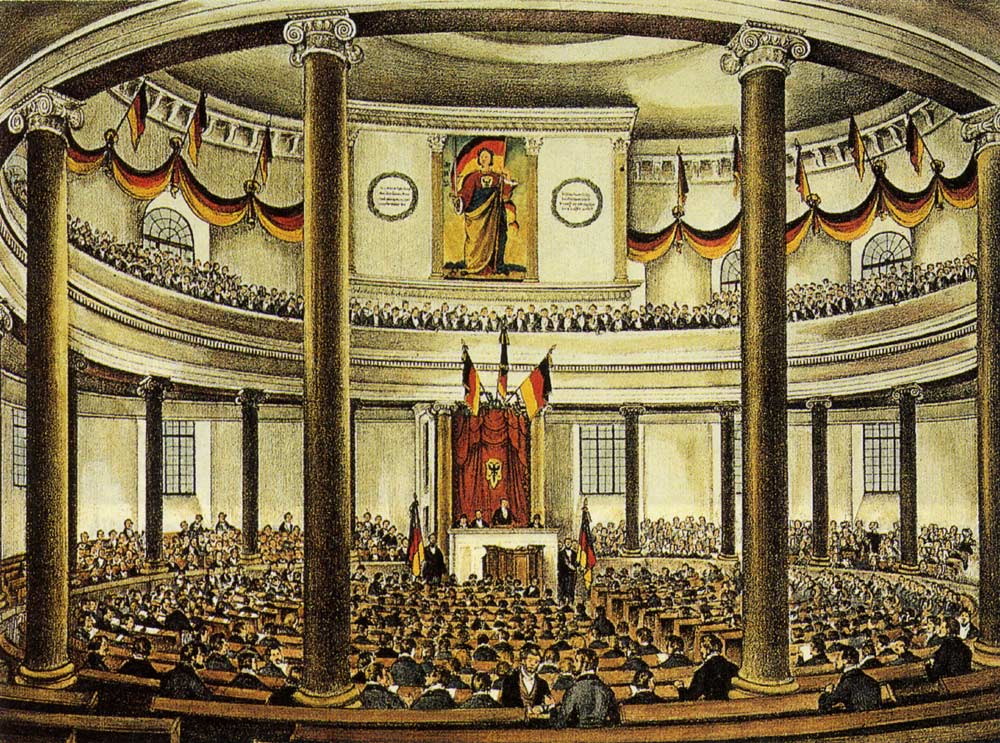

But even more important was the attempt to achieve political unification through a national assembly representing all of Germany. Elections were held soon after the spring uprising had subsided, and on May 18 the Frankfurt National Assembly met in Frankfurt am Main to prepare the constitution for a free and united fatherland. Its convocation represented the realization of the hopes that nationalists had cherished for more than a generation. Within the space of a few weeks, those who had fought against the particularistic system of the restoration for so long suddenly found themselves empowered with a popular mandate to rebuild the foundations of political and social life in Germany.

Once the spring uprising was over, the parties and classes that had participated in it began to quarrel about the nature of the new order that was to take the place of the old. There were sharp differences between the liberals and the democrats. While the Frankfurt parliament was debating the constitution under which Germany would be governed, its following diminished and its authority declined. The forces of the right, recovering from the demoralization of their initial defeat, began to regain confidence in their own power and legitimacy.

By the time the Frankfurt parliament completed its deliberations in the spring of 1849, the revolution was everywhere at ebb tide. The constitution that the National Assembly had drafted called for a federal union headed by a hereditary emperor with powers limited by a popularly elected legislature. By the summer of 1849 the revolution, which had begun a year earlier amid such extravagant expectations, was completely crushed.

Source: The age of Metternich and the era of unification, 1815–71.