Beautiful family festivals cast a beneficent light like brilliant sparks of illumination, over the whole lives of the united friends of education.

On St. John’s Day 1817, the school established at Griesheim by Friedrich Froebel to educate his nephews moved to a farm at Keilhau. There was much building and arranging to be accomplished. The material difficulties after the erection of the large new buildings were removed when Froebel’s prosperous brother in Osterode decided to take part in the work and moved to Keilhau. He understood farming. By purchasing more land and woodlands, the farm was transformed into a considerable estate.

Heinrich Langenthal and William Middendorf, his comrades from the Lützow Free Corps joined this happy family institution. A small circle of parents entrusted the care of their children to this school.

As a “living memorial” for the 300th anniversary of the Reformation two descendants of Martin Luther were educated at Keilhau. Georg Luther went on to study theology. Ernst Luther became a sculptor and made the sphere, cylinder and cube as the gravestone for Friedrich Froebel.

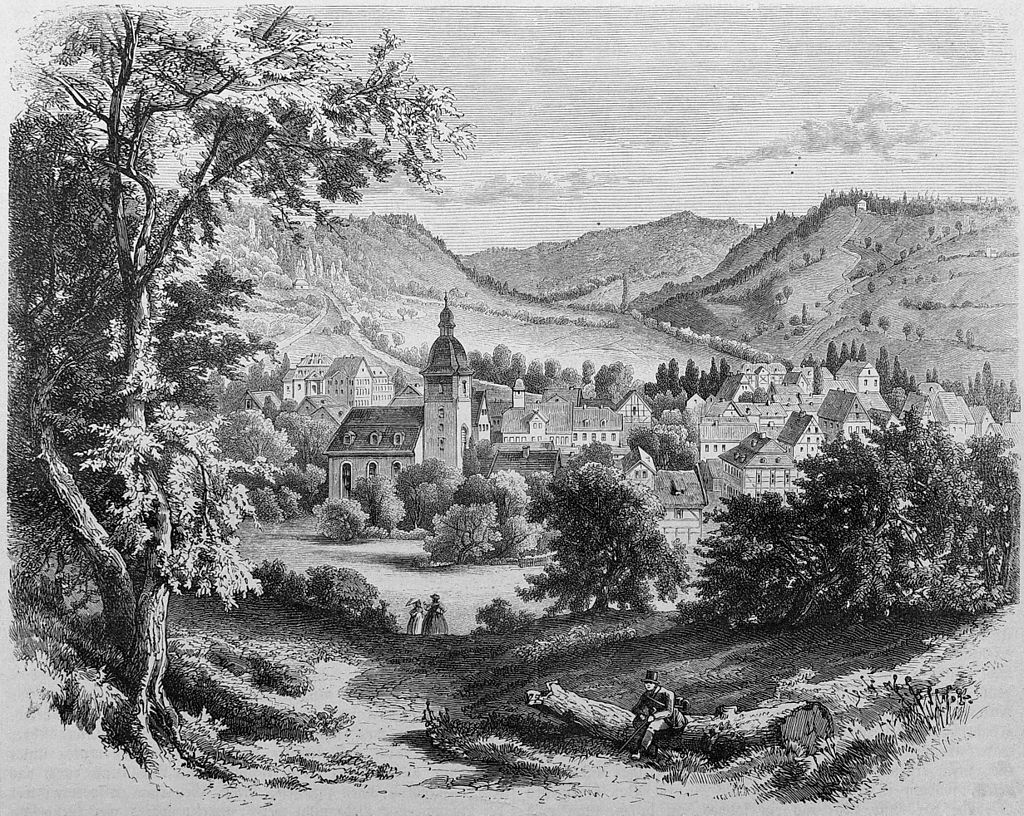

The new institute prospered rapidly. The renown of the fresh, healthful life and the able tuition of the pupils spread far beyond the limits of Thuringia. It was not only the open air, the forest, the life in Nature which so captivated new arrivals at Keilhau, but the moral earnestness and the ideal aspiration which consecrated and ennobled life. As devout Christians, they created ways to live together in peace and harmony with each other and nature. They shared lives of inward joy in this quiet, peaceful valley in the Thuringian forest.

Many paths for the ascent of the encircling mountains, provided opportunities for students and teachers to look down from these heights on what they were striving to achieve.

William Middendorf and Albertine Froebel, a niece of Friedrich Froebel married in 1826.

The Founders of the Keilhau Institute

I was well acquainted with the three founders of our institute: Fredrich Froebel, Middendorf, and Langethal. The two latter were my teachers. Froebel was decidedly “the master who planned it.”

When I came to Keilhau, he was already sixty six years old, a man of lofty stature. His features bore the impress of his intellectual power so distinctly that the first glance revealed the presence of a remarkable man. His face seemed to be carved with a dull knife out of brown wood with a long nose, strong chin, and large ears, behind which the long locks, parted in the middle, were smoothly brushed. “Come, let us live for our children,” beamed so invitingly in his clear eyes. His voice and his glance were unusually winning.

He was never seen crossing the courtyard without a group of the younger pupils hanging to his coattails and clasping his hands and arms. Usually they were persuading him to tell stories. What fire, what animation the old man had retained! We never called him anything but “Oheim.” The word “Onkel” he detested as foreign.