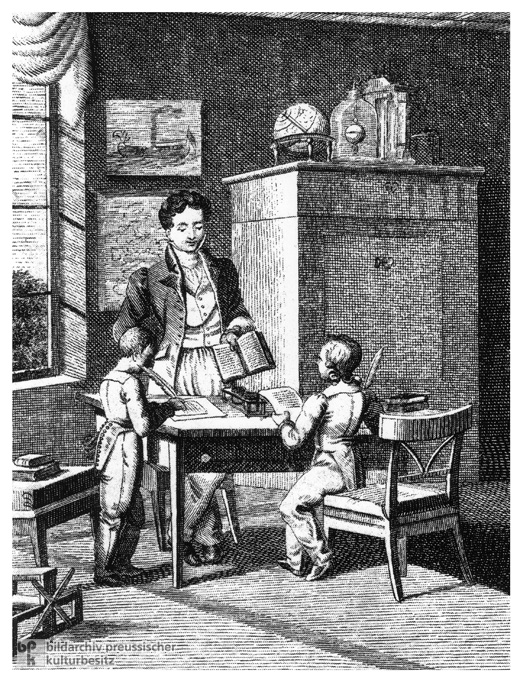

Starting in the late 18th century, an educated class developed, which defined itself more on the basis of education than material possessions.

Members of this class were often employed as civil servants, at universities, or in the free professions. Mindful of how important their education was for their own careers, parents placed tremendous emphasis on educating their children, particularly their sons. In certain cases, daughters were also given advanced educations.

The term Bildungsbürgertum was coined in the 1920s for this class for whom the concept of education as a lifelong process of human development; rather than mere training in gaining certain external knowledge or skills. For this class, education is seen as a process of continual expansion and growth of an individual’s spiritual and cultural sensibilities as well as life, personal and social skills.

The word “Bildung” is deeply rooted in the idea of the Enlightenment and has broader meaning than “culture” or “education”.

Humboldt envisaged an ideal of Bildung, education in a broad sense, which aimed not merely to provide professional skills through schooling along a fixed path but rather to allow students to build individual character by choosing their own way.

Humboldt’s model was based on two ideas of the Enlightenment: the individual and the world citizen. Humboldt believed that the university and education in general, should enable students to become autonomous individuals and world citizens by developing their own reasoning powers in an environment of academic freedom.

The University of Berlin was founded on 15 October 1810 to develop this ideal. Friedrich Froebel attended in 1812 to study mineralogy under Weiss and jurisprudence under Savigny. With other Berlin students, Froebel joined the famous volunteer corps of “Black Riflemen”, in the Prussian army against Napoleon. After the close of the war, Froebel claimed the fulfilment of the promise made to him of an appointment in the mineralogical museum at Berlin, and resumed his studies.