According to the fashion of the humanists, Jan Cizek used the latinized form of his name, Johannes Zeising.

A former monk from Silesia, Jan Cizek was educated for the Roman Catholic priesthood, studied at the Jagiellonian University of Cracow from 1504 and became a Franciscan monk at Breslau in 1510.

He and a couple of his colleagues, Michael Weisse and Johann Mönch, were influenced by the writings of Martin Luther (1483-1546). As a result the three friends were expelled from Breslau around 1517.

Zeising wrote on the topics of Scripture, baptism, and the Lord’s Supper in ways that influenced the “Colloquy of Austerlitz” held on March 14, 1526.

He wrote that the salvific spiritual presence of Christ manifested itself in living things, in the thoughts, hearts, and souls of believers.

“If salvation came through the Scriptures or the sacraments, then everyone who read or heard Scripture or received the sacraments would receive salvation and moral transformation.”

“Preaching is vain when God does not use it to do his inner work in people. For the person who is born again, the external word is a testimony of the internally experienced truth.”

“On the external or serving and the inner or essential word of God”

Zeising objected to the idea that the external, written, and preached word has the same power as the inner and essential word of God.

“The external word is a mere letter and transient voice. The inner, living word is Spirit and life. God does his work in people through the Holy Spirit how and when he wills. The outer word can transmit an external, rational knowledge of Christian doctrine and a historical, literal belief, but not a spiritual rebirth. Spiritual rebirth is a work of the Spirit; it produces a knowledge of God that is written in the human heart, and brings salvation.”

In respect to baptism and the Lord’s Supper, Zeising distinguished between the direct, salvific inner event and its external witness or signification through water baptism and the partaking of the communion elements, the same distinction that he drew between inner and outer word.

The protocol of the Austerlitz colloquy distinguished between a spiritual communion necessary to salvation and the reception of outer signs, which was not necessary to salvation:

“All believers should recognize and acknowledge two kinds of communion, one inward and spiritual, the other an external remembrance. The first, the spiritual, is necessary for the forgiveness of sins and eternal life; it happens through faith and is sufficient for salvation. The other communion is in no sense to be disparaged, but should be held in all respects according to the last will and testament of Christ.”

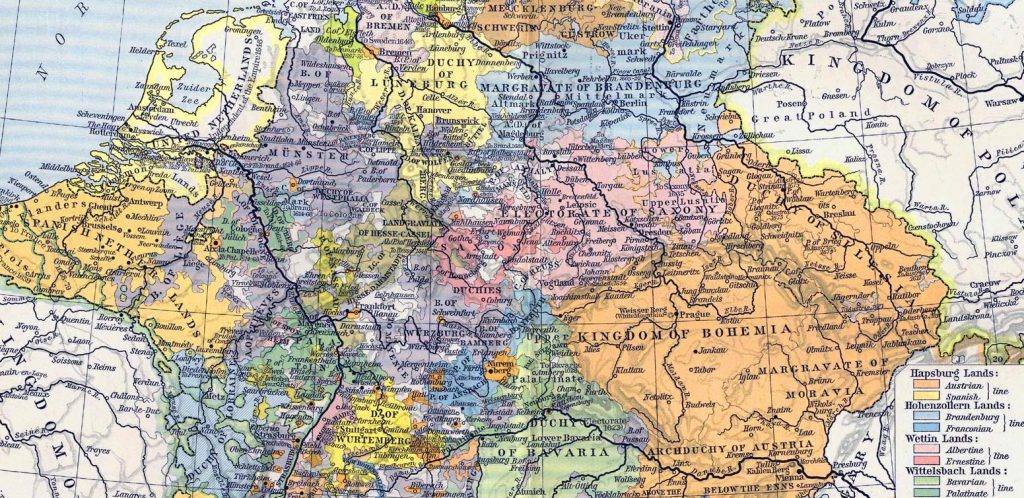

Moravia was part of the Kingdom of Bohemia, which fell to the Habsburgs in 1526. Johannes Zeising was burned at the stake on April 10, 1528 at Brunn (Brno), formerly the seat of the Moravian Provincial Diet or Estates.

The incorporation of Bohemia into the Habsburg Monarchy against the resistance of the local Protestant nobility sparked the 1618 Defenestration of Prague and the Thirty Years’ War.

In 1813 Silesia became the center of the revolt against Napoleon. The Prussian royal family moved to Breslau, where Frederick William III published the letter An mein Volk (to my people) which called the German people to arms. The experience of the war of liberation strengthened the bond of Silesians to Prussia and the Province of Silesia became one of Prussia’s most loyal provinces.